artist unknown

1873

Public domain

Eight years ago, Jan & I retired from our respective positions, she as research librarian at the wondrous Perkins School for the Blind, and me as minister of the First Unitarian Church of Providence. We shrunk our worldly goods as best we could, sold our home, and moved back to our native California.

Our intention was to be near Jan’s mom who lives in the once independent city and since 1932, a neighborhood of Los Angeles called Tujunga. (A fun fact. While it sounds Spanish, Tujunga is actually from the indigenous Tongva and means, quite suitably for us, “the old woman’s place.”)

Mom was aging and we wanted to be nearby. We explored locations as far away as four hours, but despite an interest in a co-housing community in Fresno and a love affair with the Central coast, quickly realized the foolishness of relocating across the continent, and still being that too far away for being very useful. We began to look much closer to mom, decided an hour was a good outer distance, and quickly fell in love with Long Beach.

We were able to swap pretty close dollar to dollar the price of our house in Pawtucket for a condo four blocks from the beach in the Alamitos Beach neighborhood. We loved it. And for eight years it’s been our home. I think it fair to say as far as homes and neighborhoods go we’ve never been happier with where we were.

And all things change.

While mom is in pretty good health for 96, she is 96. And in order to avoid assisted living we are moving in with her.

The move has been a trial for all of us. As I write this we’ve emptied mom’s living room and put our furniture there, the balance of the furniture, shrunk once more, is stacked in half of mom’s garage along with the remains of the most drastic cutting of my personal library ever. With about fifty or sixty or seventy books on shelving here and the last hundred or so beyond are boxed and stored with the furniture. (The balance of the rest, some eighty or so boxes are going to a home where they will be loved and cared for.)

Today we drive back to the condo to carry away (we desperately hope) the very last of our worldly goods. Friday the condo will be painted, then there’s the matter of a new carpet, replacing a damaged door to one of the bathrooms, and, well, then, are you interested in a condo in a lovely neighborhood filled with coffee shops and restaurants and interesting stuff walking distance from the beach? It will be for sale for an obscenely high price.

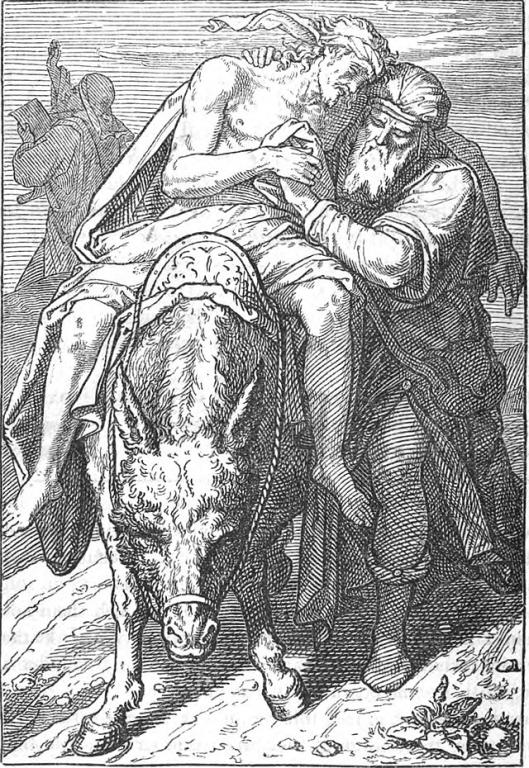

And. Well. Here we are. In the course of our lives, my mother lived with us for the last seven years of her life. My maternal auntie lived with us for the last twenty plus years of her life. And now we’re going to live with Jan’s mom.

I think about that showing up.

And I think about duty. Especially I think of the spirituality of duty.

Here I find my thoughts going to the Bhagavad Gita. It was much beloved among my Transcendentalist ancestors. Although I also love pointing out Ralph Waldo Emerson’s enthusiastic endorsement of the Bhagavad Gita as a great “Buddhist” classic. For me, in part enjoying emphasizing his mischaracterization of the great Hindu classic. But, not to be missed, Emerson’s enthusiasm for the text itself, if sorting out the differing spiritualities of the East wasn’t quite yet in place.

In the Gita I find a thread that calls to the heart and tells us something about death and birth, and life, and our choices in that place among the living. Chapter three is devoted to “karma yoga.” Here yoga means spiritual discipline, while karma means both the sum of a person’s actions, and here those specific actions that create a spiritual life. Conscience and action. In that meeting of intention and action we begin to find a sense of conscience that is both spiritual, and very much grounded in this world. In the specifics of life.

Duty.

The karma yoga of the Bhagavad Gita is the spiritual practice of action in this world. It is informed by seeking a proper understanding of what is going on. And then, well, and then acting. It is complicated. The Gita itself turns on a fratricidal war where God tells Arjuna to take up his responsibility and to fight. There is within the mess a unity. And, well. Also. In another situation where a Zen master advises a samurai to fight knowing that everything is empty. Much like Krishna telling Arjuna to fight knowing everything is the play of the mystery. But my spiritual grandfather calling us to notice there’s going to be blood. Real blood. And real widows. And real orphans.

It’s messy. It’s awful. And. And. Karma and the yoga of karma. Duty is not an easy thing. Discerning and then acting are difficult and can be very hard.

And In my own life I’ve learned we have to act on insufficient information. Pretty much always. But, nonetheless, we must act. Here is duty.

In this world even opting out, a choice to not acting, is itself an action, of course. Because everything is connected, and every choice has a consequence. Or really there are many actions coming together in any given situation, and many consequences flowing from the moment of choice. That crimson ribbon, knotted for a moment. Like blood coagulating.

And, so, conscience. What is it that we find when we dig in deep, when we look honestly at our hearts and at the world? What is it that says it would be okay to lay our life down for another, friend, or country, or something else?

Our human experience is buffeted and tossed, bruised, and banged; and somewhere along the line all of us, every precious one of us is damaged. You. me. No one escapes. If you think otherwise, you’re a master of denial. And, while denial might be a pretty good strategy for a while, in the long haul it betrays us.

Instead, I try to not turn away from the hurt, the hurts. As the Gita tells us, notice, and act. The yoga of duty.

The reason these hurts become a great hurt living a coiled serpent within us is simple enough. Our sense of these hurts rises out of our intuitions of wholeness and the fact of our separateness.

We need to see how we are separate, where babies die, and old people starve to death, where each and every one of us has experienced loss and longing. For some harder than for others, but none escapes. In this realm all of us are damaged goods. And, somehow, damaged or not, each separate thing, each of us, is precious beyond saying. That, too, is true.

Within the bruising, if we allow ourselves to experience it, we see, we taste, we know another truth.

Wholeness. Just about everyone, maybe everyone, has some body-knowing we are connected, totally connected each of us with everyone and everything else. Why is this so? I don’t know, although I have opinions. What I do know is that our sense of this wholeness comes to us unbidden out of our experience of separation. A grace. A thread, a crimson ribbon winding around our hearts tugging us in directions.

It is the source of our conscience, it tells us who we are, and it tells us our place in this world. It is the sacred text written on our hearts. We notice how our dreams are invaded by this deep knowledge of our source and home: our radical interdependence. Our quiet moments proclaim it. Instances of grace intrude it into our lives, singing the angel song of deepest connection.

Our bodies know the connection. And, so, I invite the critical step of turning our hearts to noticing this unity when it presents. Here the mysteries of duty reveal themselves.

And then, perhaps, another question comes to us. If we continue to follow the ribbon we discover a mystery: we are separate and one. A conundrum. But a reality. It’s not that we are either separate or we are connected. And with that the thread leads to another invitation, to move beyond the conundrum, beyond self and other.

Out of that wonderment the great invitation sung to us from before the creation of the heavens and the earth. The words and the music proclaim a connection deeper than two or one. Found as we engage our lives, our responsibilities, as we step up.

A healing way that can be found as we explore the connections, as we follow the thread, as we trace along the ribbon.

Our world can go in several different ways. Most of them not good. All of them dangerous.

But we have some guidance and we have some examples.

What we need to learn in our lives both as individuals and citizens follows the same course. And that course was so wonderfully sung to us by the poet Mary Oliver.

“To live in this world you must be able to do three things: to love what is mortal; to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.”

Here we are, mortal beings. We are herd animals. We need each other. For so much from care in our infancy, to the gift of language, to the skills it takes to survive, to others to love and be loved by, to having caring hands to deliver us back to the soil. All of that mortal mortal stuff.

For me I experience this and I experience many many things. But most of all, an electric current running through it all is that most human thing: love.

And then there is the current of our actual lives. The bones that give us our shape. Family, of course. For good and for ill. Our nation states, for sure. For good and for ill. And, our shared humanity and our shared obligations as the conscious creatures for the care of this whole beautiful fragile world. All of it. For good and for ill.

Here I find our duty. To care and to be engaged.

We need the larger perspective. We need to avoid the blandishments of turning away from the perceived other.

But if we love and keep loving. If we show up. And we show up again.

If we learn the art of letting go even as we hold to our bones, then things happen.

Here is our duty.

The yoga of duty. The spirituality of duty.