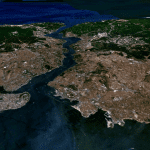

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

This morning, we went first to the Hagia Sophia (Ἁγία Σοφία)—also called, depending upon the language, Ayasufya and Santa Sophia and Sancta Sapientia and the Church of Holy Wisdom (or Divine Wisdom). Sophia isn’t the name of a female saint; it is the Greek equivalent of English “wisdom.”

After its completion in AD 537, Hagia Sophia was the largest Christian church in the world for roughly a thousand years—only being supplanted in that rank in the early sixteenth century by Spain’s Cathedral of Seville, which was in turn beaten out by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (or Vatican City) shortly thereafter. It is said that, when the Emperor Justinian I (“the Great”) entered the building for its dedication, he thought of the ancient temple of Jerusalem and remarked “Solomon, I have triumphed!”

I’m in awe of the rich history not only of Istanbul but of Hagia Sophia specifically, and of the fact that Hagia Sophia has stood basically intact for nearly a millennium and a half in an area that is extremely active, seismically speaking. The Anatolian transform fault system has been ranked as perhaps the most active in the world; it separates the Eurasian plate from the Anatolian plate in northern Turkey. But when we walk into the great church today, we are walking into the same building that Justinian saw.

The present Hagia Sophia is the most recent of three church buildings to be erected, successively, on the site. Its immediate predecessor was destroyed during the dramatic Nika Revolt of AD 532. The prolific St. John Chrysostom, archbishop of Constantinople, preached in one of the two earlier buildings. (Chrysostom means “golden mouthed” in Greek; it is a tribute to his legendary eloquence.). For a few decades after 1204, as a result of the disgraceful Latin conquest of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, it became a Roman Catholic cathedral. (The Eastern and Western churches had mutually excommunicated each other by this point, and there was no love lost between them.) After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the Hagia Sophia was turned into a mosque. (Hence the four large minarets that are now attached to it.) In 1935, as part of the modernizing and secularizing reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, it became a museum. In 2020, as part of the Islamizing measures enacted by the current Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, it became a mosque yet again. I was relieved, although we were not allowed to climb to the higher floors, that the paintings and mosaics were somewhat less concealed than I had expected and feared.

Next, we visited the Istanbul Archeological Museum, which is said to be Türkiye’s largest museum. (This was my first time at the Museum.) Its collection includes more than a million artifacts, including one of the three serpent heads from the serpent column at the Hippodrome, but that portion of the Museum was apparently closed. At least, I didn’t see it. Nor did I see the famous Treaty of Kadesh, which is located there. Still, the Museum is a wonderful place, very clearly and elegantly displaying what we could see of its treasures. Its collection of classical sarcophagi is amazingly good; they look new. And its treatment of Troy is fascinating, including an aerial recreation that shows that city’s famed and fateful history from earliest times.

Our last stop was to the Spice Bazaar or Spice Market, which was built in the 1660s. In Turkish, it is known as the “Egyptian Bazaar” (Mısır Çarşısı), because it was built with revenues from the Ottoman province or eyalet of Egypt. It is one of the most colorful bazaars in Istanbul, offering innumerable souvenirs, spices, dried nuts, and more. It was in the Spice Market, years ago, that I first understood why, after his arrival in Narnia, Edmund would betray his siblings, Peter and Susan and Lucy, to the White Witch in exchange for Turkish delight. When I first read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I couldn’t understand his betrayal. But now I definitely do.

I was disappointed that we were unable to visit the Great Palace Mosaic Museum, as we had originally thought to do. (It closed last month, for something or other.) It is an actual part of the Great Palace complex—the Μέγα Παλάτιον (Méga Palátion) of Byzantine Constantinople. (It was also called the Ἱερὸν Παλάτιον [Hieròn Palátion], or “Sacred Palace.”) It was first laid out in the southeastern end of the peninsula by the emperor Constantine in the area that is now called “Old Istanbul,” the former ancient Constantinople proper. The Great Palace served as the residence of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine emperors until 1081, and was the center of imperial administration for nearly seven hundred years.

Only a few remnants and fragments of its foundations have survived into the present day. The site of the Great Palace Mosaic Museum is one of the few extensively excavated sections of the ancient palace, and its mosaic floor is one of the best surviving examples of the art of Late Antiquity.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Even more, I was enormously disappointed that we could not take our people to the relatively tiny Chora Church, which has been one of my favorite places in the city since my first visit, particularly for its remarkable Christian frescoes and mosaics. It is located in the Edirnekapı neighborhood of Istanbul, very near the place that, as I mentioned in a previous entry here, some of us visited on the first day of our arrival, where the Ottomans first breached the massive land walls of Constantinople on 29 May 1453. But the original Chora was built in the early fourth century as part of a monastery complex that was outside the city walls of Constantinople. Those walls had been erected by Constantine the Great to the south of the Golden Horn as part of the original founding of the city. Hence, its name: Literally translated, the church’s full title was The Church of the Holy Saviour in the Country or The Church of the Holy Redeemer in the Fields (ἡ Ἐκκλησία τοῦ Ἁγίου Σωτῆρος ἐν τῇ Χώρᾳ, hē Ekklēsia tou Hagiou Sōtēros en tēi Chōrāi).

However, when Theodosius II built his famously formidable land walls in AD 413–414, the church became incorporated within the city’s defences. Even so, though, it retained the name Chora. The situation is rather like that of London’s St. Martin-in-the-Fields, the forerunner of which was located in the farmlands and fields beyond London’s city wall. The current neoclassical church dates to the early eighteenth century and sits at the northeast corner of Trafalgar Square, which is surrounded by the City of Westminster, London. Another comparison might be made to Rome’s Basilica Papale di San Paolo fuori le Mura (the “Papal Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls”), which was founded by Constantine the Great (!) over the likely burial place of the Apostle Paul. Its name derives from the fact that it lies outside the city’s third-century Aurelian Walls, but it is now very much a part of the city of Rome.

In its current form, the Chora dates mostly from the eleventh century, though it was substantially rebuilt in the fourteenth century, which is also the period of its great mosaics and frescoes. By far my favorite of those is the fresco of “The Resurrection,” which appears above.

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, and probably after about 1500, the Chora was transformed into the Kariye Camii (or “Kariye Mosque,” the word Kariye deriving from the Greek Chora). It remained a mosque until the Turkish government declared it a museum in 1945. In 2020, though, it was again declared to be a mosque under the Islamizing government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Sigh. It is now closed indefinitely for “restoration.”

Have I mentioned before that this is an astonishing city?

In its heyday during the Byzantine period, Constantinople was absolutely enraptured with theological debates. At least, so it was according to St. Gregory of Nyssa, who famously described it thus in his Oratio de deitate Filii et Spiriti Sancti, (= Oration on the deity of the Son and of the Holy Spirit) which is printed in Patrologia Graeca 46, where the passage is on col. 557, section B:

Everywhere, in the public squares, at crossroads, on the streets and lanes, people would stop you and discourse at random about the Trinity. If you asked something of a moneychanger, he would begin discussing the question of the Begotten and the Unbegotten. If you questioned a baker about the price of bread, he would answer that the Father is greater and the Son is subordinate to Him. If you went to take a bath, the Anomoean bath attendant would tell you that in his opinion the Son simply comes from nothing.

From the Spice Market, our bus picked us up and took us to the Istanbul Airport, where we caught a flight down to the southern Turkish city of Adana. It is my first time here. I’m excited.

Posted from Adana, Türkiye