My current work on Lived Religion constantly reminds me of how very similar are the things that people do in different religious traditions, however widely separated by place or era. This in turn has got me quite deeply into the very sizable literature on the scientific explanations for religious behavior, including the Cognitive Science of Religion. What I can say here in a blogpost or two is pathetically slim when set against the very large literature, but let me list a couple of major insights of that field of study. In particular, I will address the question of how far these recent arguments and discoveries challenge the whole basis of faith, or of faiths. I won’t say too much about that here, but briefly – don’t worry, the Anxious Bench is not about to sign up with the Patheos Atheist Channel just yet.

I have posted online a bibliography of recent publications on this area, and do note how very current this literature is. Witness the number of books from major publishers with copyright dates of 2022-2024. This is a very lively field indeed.

The Normality of Religious Behavior

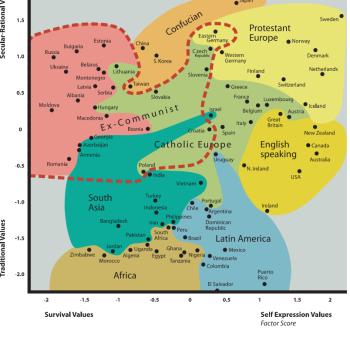

Religious traditions and creeds differ very widely, but types of religious behavior and belief are very common indeed. In many parts of the world, and in diverse historical eras, some motifs are so widespread that they seem to arise naturally and intuitively, and prolifically. Those commonalities would include ideas about sacred space and charismatic individuals; about the proper ways of showing respect to holy things; about ideas of pilgrimage; about the quest for spiritual healing; about using portable objects to enhance benefits and protect against evils; about the power of fasting and regulating foods; and about various forms of divination. Those elements appear naturally, whether or not they are absorbed in some larger agglomeration of beliefs, and still less of formal credal statements.

Noting such powerful impulses, scholars have long theorized about biological and evolutionary bases of religious belief, even proposing concepts such as a “God Gene.” Might the religious drive itself might be natural and inborn, as much an instinct as any other? Such grand claims have attracted much criticism, usually because they are reductionist and mechanistic, and they remain controversial. Having said that, many aspects of human behavior and shared experience heavily predispose us to ritualistic responses, of the kind that so often characterize lived religion.

That question found new foundations with the emergence of sociobiology and the latest variants of evolutionary theory. From the early 1990s, a number of scholars created what has become a thriving discipline of the Cognitive Science of Religion, commonly abbreviated to CSR (the phrase dates to 2000). This extensive literature addressed such issues as the obvious human need not just to imagine and portray supernatural beings but to locate their activities, and to believe in the crossing of seemingly impermeable boundaries, notably that dividing life and death. Abundant evidence now shows how readily and naturally people in virtually all societies, and all eras, naturally “go religious” as circumstances demand, and likewise resort to ritual behavior.

Universal Truths?

Some “religious” ideas have what we might call a common-sense quality. Most basic to human consciousness is the sense of individual self: we exist, we are. This self-consciousness encourages a belief in an absolute reality of self external to the body. That does not mean that all societies have a belief in personal immortality, since they do not; but the notion of a soul or souls separate from the vehicle of flesh and blood is very common.

In addition, we are born and we die. This core identity that we possess must have come from somewhere, some other realm, and it must continue somewhere in some form. Intellectually, we know that we will die, but it is literally impossible for us to imagine our own non-existence. We know that our identity must continue somewhere, in some form, giving rise to widespread ideas of an afterlife.

Moreover, humans are children for a very long portion of their existence. Compared to other mammalian species, we spend a large proportion of our lives in a state of utter physical and psychological dependency on a larger and all-powerful figure or figures. Observers have long suggested that this fact contributes mightily to our willingness to hypothesize the existence of gods, angels, or supernatural sources of wisdom and guidance. The near-ubiquitous quality of revered supernatural mother figures presumably originates in this context.

Only yesterday, Ross Douthat offered a thoughtful column in the New York Times on the core question of “Where Does Religion Come From?” Among other opinions, he summarized the views of Paul Bloom:

Because “we perceive the world of objects as essentially separate from the world of minds,” it’s easy for us “to envision soulless bodies and bodiless souls. This helps explain why we believe in gods and an afterlife.” And because we look for intentionality in human beings and human systems, we slide easily into “inferring goals and desires where none exist. This makes us animists and creationists.”

Seeking Meaning

To pursue Bloom’s point, we do indeed look for meaning and connection, and (despite all evidences to the contrary) we find them. Psychologists use the technical term of pareidolia to describe the human tendency to impose meaningful visual patterns on vague and seemingly random shapes: this would include for instance identifying human features in natural objects. More generally, apophenia leads us to discern patterns in other kinds of phenomena where none in fact exist.

Related to that is our intuitive need to discern rational agency and purpose. Much remarked in this context is the fact of “agent detection,” the tendency of animals, including humans, to assume the intervention of some intelligent agent: it is sometimes summarized as “if you hear a twig snap in the forest, some sentient force is probably behind it.” Such a belief had a real evolutionary advantage, as it proved useful in enhancing awareness of likely predators. Michael Shermer writes of the human tendency “to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency”, which he terms agenticity. In a great many societies, we believe that things happen to us not through happenstance, but through the action of others, conscious or otherwise. Among other things, the idea of cause and effect gives rise to notions of witchcraft, with all the attendant cures and protections.

In other ways too, we project our known human realities onto the inanimate and non-human world. We assume that other beings and things must operate and think and act in ways comprehensible to us, even when we know rationally that this is not the case. In his classic statement of a cognitive theory of religion, Stewart Guthrie stressed that religion can best be understood as “systematic anthropomorphism–that is, the attribution of human characteristics to nonhuman things and events. …. Religion, he writes, consists of seeing the world as humanlike.” Guthrie’s important 1993 book bore the evocative title of Faces In The Clouds.

Potentially “spiritual” concepts extend still more widely, to ideas of reciprocity and exchange. When teaching Religious Studies, I often ask students how often they have attempted to plead or bargain with their cars or ATM machines, and few deny the behavior. Principles of anthropomorphism and animism seem firmly rooted in the human mind. They lead us not just to imagine spiritual beings but to make them as human-seeming as possible, and to create material representations of them, to make them channels for direct communication.

Altered States

A sense of holiness may also be claimed as universal. The science of religion suggests that we are programmed to feel awe and exaltation, so that we acknowledge or imagine the presence of the special and holy. Further, we tend to locate these qualities in particular persons, events, and places. Likewise, we know dread as well as awe, and readily imagine the evil inherent in places, to be shunned or tabooed.

Alternate states of consciousness (ASC) play their role, including as they do trance states, ecstasies, hallucinations, dissociative experiences, out of the body experiences, sleep paralysis, near death experiences, and various peak experiences. But as as Pieter Craffert remarks,

A leading early-21st-century ASC researcher pointed out that the study of ASCs is currently at a similar stage where botany was before Linnaeus proposed his taxonomy; namely, a collection of interesting observations lacking enough organization and integration to make theoretical and empirical sense of them.

Depending on the society, there are many ways of exploring such altered states, including fever, trance, drunkenness, or extreme stimulation. In such states, people believe they see visions and rise above time, to defy the borders between life and death. They undertake shamanic journeys and sky journeys. Ritual behavior around the world tends to have many resemblances across cultures.

In mental illness and personality disorders, we see alterations of character and behavior that all too plausibly indicate the presence of new and hostile spirits who have displaced the true owner of the body in question. It is no great leap to crediting evil spiritual forces with the causation of all diseases of the mind and body.

Spiritual approaches to healing arise naturally, and they readily become attached to special places. It is very natural for us to travel to places we believe to be sacred, to make offerings for spiritual rewards to be found there. We readily locate holiness in things, even portable objects, which can be used to carry away the special qualities inherent in such places.

Telling Stories

Our forms of religious story-telling and interpretation can likewise be traced to universal human characteristics. The fact of dreaming tells us of other states of consciousness and reality beyond the everyday world, as the boundaries of reality collapse: animals speak, the dead walk. We see here confirmation of higher and lower realms. In terms of primal or indigenous religions, these facts sustain the belief in the Otherworld, the Dreamtime, in shamanism.

When people try to convey the truths they learn in these other states, they do it by the standard means that humans try to make sense of the incomprehensible: they tell stories, make myths and legends. As Andrew Greeley remarked, religion was “experience, symbol, story (most symbols were inherently narrative), and community before it became creed, rite, and institution. The latter were essential, but derivative.”

Understanding and elucidating the “building blocks” of religion is an essential project. Or to shift the metaphor, establishing the underlying vocabulary from which more formal religions are constructed. Such basic elements emerge most obviously in the primal, indigenous, or traditional faiths, but they remain firmly in the world religions, and indeed in very modern secular societies. (Labeling such older religious ways is a controversial endeavor, and terms like “primal” are rightly criticized for the suggestion of primitivism). To continue the linguistic metaphor, such survivals serve as a kind of “interference,” as when one’s original speech affects speaking patterns when one learns and speaks a new language.

Such indigenous or primal ways are transformed by the coming of literacy, and the transition to scripture- and clergy-based religions, but older forms are strikingly durable and persistent.

With that in mind, take a look at the bibliography I mentioned, and see some examples of the kind of work that people are doing. Look for instance at the amount of work being done applying these theories to Biblical narratives, for instance in terms of visions and spirit possession, and the parallels to other far-flung societies around the world. We also note titles such as Dominic Johnson’s God Is Watching You: How the Fear of God Makes Us Human; or John C. Wathey, The Illusion Of God’s Presence: The Biological Origins Of Spiritual Longing. As a title, I still like Lewis Wolpert, Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: The Evolutionary Origins Of Belief.

Explaining Religion?

But do these various insights offer a complete explanation of our religions? The basic idea that we naturally imagine gods and spirits is integral to Tanya M. Luhrmann’s fascinating How God Becomes Real: Kindling the Presence of Invisible Others. But she also

notes that none of these people behave as if gods and spirits are simply there. Rather, these worshippers make strenuous efforts to create a world in which invisible others matter and can become intensely present and real. The faithful accomplish this through detailed stories, absorption, the cultivation of inner senses, belief in a porous mind, strong sensory experiences, prayer, and other practices. Along the way, Luhrmann shows why faith is harder than belief, why prayer is a metacognitive activity like therapy, why becoming religious is like getting engrossed in a book, and much more.

I would add that anything Luhrmann writes is eminently worth reading: see especially her 2012 book When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God (Knopf).

Being human makes us naturally understand things in religious ways, even if we reject any formal or institutional religious affiliation. We are conditioned (programmed) to look for things that we understand as holy, to project holiness onto particular people or places, to feel awe in their presence, to deny the reality of barriers separating life and death, and we will continue to do so even if all existing creeds have evaporated. Magic, animism, and anthropomorphism are all deeply grounded in our minds, whatever our cultural background. We need the holy, however we imagine it.

That is a long way from challenging the reality of religious faith or meaning as such, but it must complicate our understandings of those issues. For one thing, it means that faith in some form is not going away, however much it may mutate into forms that are presently strange to us. But the worst mistake that religious thinkers or believers could make is just to ignore these insights, and pretend that they never emerged.

I’ll talk about the implications of all this in my next column.