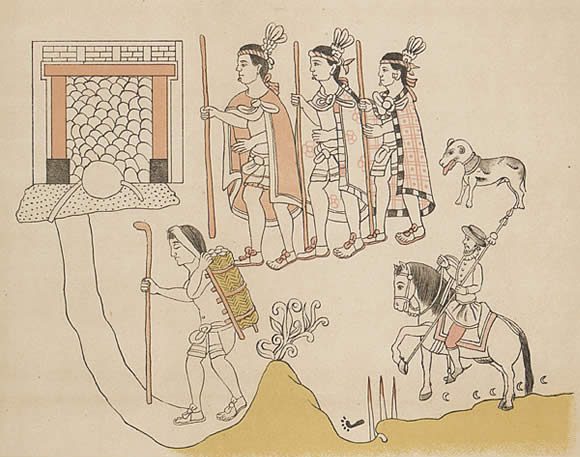

It keeps cropping up in my classes. Perhaps we’re studying about reported Aztec visions of the arrival of “white men” in the Western Hemisphere. “Do you think this really happened, Professor Diller?” someone is bound to ask. And then we stop to have the conversation about miracles—a conversation it seems I have almost every semester in all my courses. Just this week, in my class on the Mediterranean world 600-1600, a student wanted to know if I thought Muhammad was lying about hearing the voice of God, or if he was just delusional.

Historians of the pre-modern world are deeply aware that one of the largest challenges our students face is trying to understand the sacred and profane in the past. In the modern world, we have very few communal sacred spaces, items, or practices. Even those of us in a Christian community often practice a kind of “low church” liturgy that is casual and accessible. It is very challenging for me and my students to read at face value the claims of folks in the past, who said they felt compelled to do something because of the demands of the divine or because of the omens they saw. Smart young people assume everyone in the past is being motivated by power or money, not by sincere belief.

So that’s two problems for the history teacher connected to the supernatural: Both the fact that moderns don’t take it seriously, and that students are tempted to try to prove whether a magical experience did or didn’t happen that way. The first one I will try to address in the classroom. I want my students to imagine a world in which the magical, miraculous, and sacred/evil are abroad everywhere in the world. That’s the context of the people they are studying. This requires them to try to “un-know” things like what causes an eclipse or how mass psychosis works. We need them to come face to face with the world they are studying.

As for trying to “prove” whether something happened—that’s not always possible, and it isn’t necessary for developing an understanding of the past. Most of the time I can’t really know for sure what happened about the most interesting elements in the lives of the people I study. The nature of my evidence can preclude Enlightenment-style certainty about the things that we (or my students, anyway) might consider most important in life: love, fear, anger, motivation. Did Eleanor of Aquitaine have an affair with her uncle? Was Charles II a secret Catholic? Were the women accused of witchcraft really possessed by demons? When I can’t “really” know about some element, I choose to reflect the evidence that I have. “So-and-so said that they saw a priest going to Charles II’s room the night he died” or “Adultery was listed among the crimes for which King Louis was justified in annulling his marriage with Eleanor.”

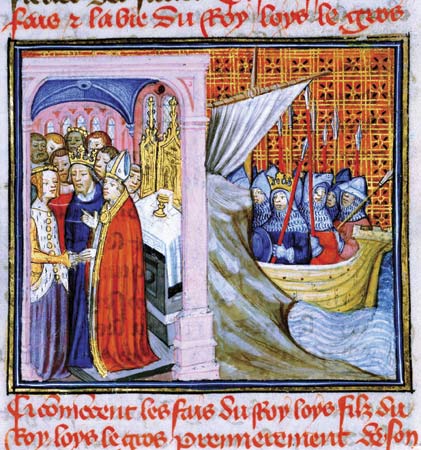

The same is true of supernatural events. I don’t know what, if any, supernatural events accompanied the Battle of Hastings, but I do know that both sides saw stellar activity as an omen in their favor. Just before some of the Viking raids into England, monastic records also described appearances in the sky of horses running or dragons flying. I don’t see it as my job to prove whether these events happened, but to talk about the people who believed those things. What might it mean to people that they believed this had happened? We don’t have any “unbiased” sources (how boring that would be!), but we can take the different perspectives and come to an understanding of how things might have played out the way that they did—why people responded as they did and what options they thought they had.

As a Christian, I want to be careful about discounting the supernatural in stories that don’t happen to coincide with my own belief system. If I am too quick to say, “those supernatural stories that show up in Inquisition documents are probably just describing some sort of hallucinogenic state,” then I am setting myself and my students up to write off the action of the supernatural in human society in all times and places. I begin to function as if the materialism of Enlightenment ways of knowing is the only way to view the world. It will be harder for me to believe in anything one could call a miracle. And this leaves the world and my experience of it not only less rich, but also devoid of the whispers of the divine in my life. I want my students and I to imagine a world where surprising glimpses of the transcendent are conceivable. That means suspending a constant criticism of the magical or “impossible” in my sources.

One thing I find interesting is that at some level, most of my professional work requires trust, of a certain kind. As a historian, I must trust my sources—I can’t assume everyone was lying all the time, or I lose the ability to function. But I also must treat the texts equally in my scrutiny. No single report can trump all the others—I look for corroboration between pieces of evidence. My devout students are sometimes tempted to say certain events, usually things they approve of, are “miracles” of God that can be proven, and other things are “just” superstition that can be discounted. This is playing favorites. While we can often come to a reasonable argument on one side or another based on the preponderance of evidence, we must be humble and contingent about our conclusions when we are functioning as professional historians. These are skills I first learned within my Christian upbringing: trusting ancient written sources, reading texts critically and comparatively, and being humble about how much I actually can ultimately attest to.

It isn’t always easy to acknowledge those different versions of evidence. I often want to find a way to integrate all my ways of knowing so that I don’t “know” one way in one context and “know” differently in another. But it is in fact true that I “know” the Civil War occurred in a different way than I “know” my husband loves me. I “know” who to vote for in the city council elections differently than I “know” how to treat my sinus infection. As a Christian looking for evidence of God around me, I am quick to recognize the supernatural. As a historian evaluating multiple sources of evidence, I suspend judgment about what is beyond material proof, in order to understand the rich and multivalent lives of my subjects. My first duty is to them and to attempting to be honest about the world they inhabited. This is challenging but rewarding.