An excessive heatwave blanketed New York in July 1911.[1] Acton Griscom, a month shy of his twentieth birthday, was grateful for the evening sea breeze on the porch of The Oriental Hotel. He was excited for the future.[2] The letter he just sent was, admittedly, a rather bold procedure, but there was no other course to take. He did what needed to be done. His request to borrow a priceless object from Lord Harlech was unconventional, but his letter followed all the rules of expected decorum, both identifying himself, and describing his proposed work.

The Oriental Hotel. (NYPL.)[3]

He explained that he was a Junior at Columbia University, a scholar of medieval history and mysticism, and that he had declared his intention to take orders in the Episcopal Church.[4] He also lamented that no accurate (or critical) text of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae had hitherto been published.[5] It was important, Acton explained, because it was the earliest of texts which referenced King Arthur and the wizard Merlin, and therefore important to mankind.

The young scholar had already assembled the known editions of Geoffrey’s manuscript as to compare their contents. Since it was impossible to collate the whole group of forty-eight twelfth-century manuscripts, the question presented itself as to which two or three representative manuscripts should be selected for publication. Comparing some test passages from various manuscripts with some of the existing Welsh versions available to him, Acton was convinced that Monmouth’s work had appeared in various editions. By studying the rotographed Cambridge Manuscript, he was able to date its publication to before June 1138, marking it as the oldest surviving copy known. The second-oldest copy, Acton concluded, was the Bern Manuscript. With the first and second manuscripts determined, it remained only to contrast them with a fitting example of the later (and more stereotyped) form which The Historia Regum Britanniae assumed.[6] To complete his work, Acton needed a particular manuscript that was in the private library of Lord Harlech—the Porkington 17.[7]

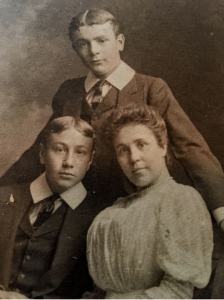

Ludlow, Acton, and Genevieve.

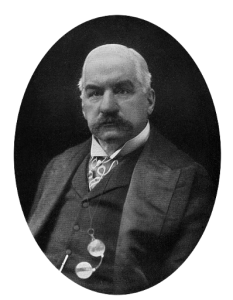

The days turned into weeks, and weeks into months. Acton had all but given up hope when his phone rang one December day. It was from J.P. Morgan. By a strange twist of fate, America’s leading financier would play a role in in this modern Arthurian romance. Having met with Lord Harlech, Morgan assumed personal responsibility for the rare Welsh texts, and carried the velum back to America in the breast pocket of his over coat. Porkington Manuscript would be deposited in the new Morgan library where Acton could conduct his study.[8]

The Morgan Library, 1906.

~

In the 1880s Acton’s maternal grandfather, the late General William Ludlow, was ordered to Philadelphia to assist the river and harbor improvement project. Stationed at 1125 Girard Street, Ludlow’s thorough study of the district’s needs enabled comprehensive projects for the improvement of all the navigable waterways.[9] It was not so long after his expedition into the Black Hills. Ludlow would have talks with the leading scientific authorities. It was around this time that Ludlow showed interest in Theosophy. (Blavatsky herself once resided at 1111 Girard Street when she lived in America.)[10] Ludlow discussed Zoellner’s “Transcendental Physics” and the writings of Blavatsky with his friend, Major Otto E. Michaelis (an authority on practical chemistry and electricity, and a prominent member of the Engineers’ Club of New York City.)[11] For Ludlow, Theosophy explained (among other things,) “the history and nature of extinct civilizations and races unknown save by their relics, and the causes of their extinction: the unequal development of existing civilizations…”[12] Given his experience in the Black Hills, this must have weighed on his mind.

The call for improvement was, in large part, signaled by Acton’s paternal grandfather, an energetic businessman named Clement Acton Griscom Sr. Born into an old, well-established Quaker family in Pennsylvania, Griscom entered the financial world at sixteen, beginning as a clerk with the shipping firm of Peter Wright & Sons and making partner by the age of twenty-two. His rise up the corporate ladder can only be described as meteoric. He would, in later years, be described as “typical of that class of Americans, who, starting without wealth or influence, have become captains of industry by sheer force of work consistently directed toward one end. He is one of the richest men in the United States, yet he began life with practically no capital other than good blood and wholesome habits.”[13]

J.P. Morgan.

After the Civil War, J.P. Morgan’s Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), was eager to develop international trade using the Port of Philadelphia. Raw exports ( petrol, grain, and iron,) were found in excess in Pennsylvania, but there was no reliable steamship transportation to facilitate trade. Griscom, with the support of the PRR and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, urged Philadelphia commercial interests to support mercantile development. In 1871 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted a charter to Griscom for the creation of the International Navigation Company (INC.) The primary financial backer, the PRR, would provide free wharfage and amenities. In 1872, Griscom and representatives of the PRR held a conference which resolved to establish a steamship line from Philadelphia to continental Europe. Antwerp was chosen as the European terminus—a once bustling port, by the 1870s excessive silting had prevented any steamer from accessing the harbor. With new dredging technology designed by engineers like Ludlow, a solution had presented itself. The decade of 1873-1883 brought many advances for the INC. The sizes of their ships doubled, and the number of their passengers increased tenfold. Consolidated transatlantic and transcontinental services provided by the INC and the PRR proved popular with European immigrants, for a single ticket could carry a passenger from Central Europe to Chicago.[14]

The effect of Ludlow’s work soon became known to the citizens of Philadelphia, and he worked with and among the “honored names of the modern ‘knights of industry.’”[15] Ludlow even took his daughter Genevieve (Acton’s mother) with him “to visit his friend J.P. Morgan.” (A fond memory that Genevieve would never forget.)[16] Ludlow, being a fixture of Philadelphia high society, attended “notable receptions” with men such as Morgan and Griscom—the latter’s son, also named Clement, was being groomed for business at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Finance.[17] “Clem,” as he was known, was a young athletic man who, incidentally, developed an interest in Theosophy around the same time as Ludlow. Ludlow took a liking to Clem, and so did his daughter. In November 1888 Genevieve and Clem were engaged. Clem, (Acton’s father) must have been anxious at the time, for the announcement of the engagement was concurrent with the announcement by Madame Blavatsky of the formation of the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society. (Some of the teachings of this section regarded a secret brotherhood of enlightened beings, and an inner order of devoted disciples.) Clem sent Blavatsky his pledge to enter as probationary student (chela) of this elite section but expressed his concern about allegiance to family and country.[18] (Having the same name as his father, Clem did not wish his name to be publicly connected with the Society.)[19] Blavatsky wrote back:

December 18, 1888.

I have your letter of Dec 3 inquiring about the Esoteric Sec. T.S. My old friend Mr. W.Q. Judge has been here with me & has given me good accounts of America & about you has spoken well. As you are a friend of his I can explain to you briefly.

I leave to him as my sole U.S. representative to go into matters more fully with you & all others in the Section or out of it. The “obedience to the Head of the Sec.” is solely obedience to my direction as to the method of study. None of these probationary students are put under “orders” requiring blind obedience but are required to exercise the intellect; judgment & discretion. Hence I should never ask you that which will conflict with your duties as a man or a citizen. I reserve all my “orders” to be carried out implicitly for certain chelas who are in a position not only to desire to carry them out but also whose circumstances permit it; & those chelas are those who have been initiated in a way as yet unknown to you. They reached it after long years of struggle. As this degree is probationary it is to prove & try & select out of the mass of Theosophists those who really have at heart the true desire to go forward & benefit the race. Time enough to issue orders for blind execution when I have those chelas who can execute them. Yet this degree is very serious, in this, that it begins at the foundation & is a necessary step in theosophic development. All will receive as they deserve.

I thank you for your kind expression as to my work & only hope that you may in some way find yourself able to help my brothers in America who work in the cause which is Masters Cause. One question: if you were ill & called a physician, w’d you not obey his orders? If you learnt a language w’d you not follow the directions of your professor; & as a soldier in the army those of your superior? Of course one who joins must have confidence in me otherwise better he should never join at all.[20]

Clem’s concerns were unfounded. In 1889 Clem and Genevieve were married.[21] Weeks after their marriage, both Genevieve and her father would join Clem in the Theosophical Society.[22] After a brief time working at the American Line’s office in Chicago, Clem and Genevieve returned to New York City in 1890 where they leased an apartment at The New Netherlands Hotel. It was here where their first child (Acton’s brother) Ludlow Griscom, was born.[23] The young family soon moved to Flushing, Queens, where, in 1891, Acton was born. Though he was born in the same summer in which Blavatsky had died, the movement remained active in America under the guidance of William Quan Judge, a close friend of the family whom Acton and his siblings regarded as an uncle. Acton and his brother, in fact, would be raised as Theosophists. It was the summer of 1891 where Lord Harlech makes his first appearance, and for that we turn to another member of the Esoteric Society.

HARGROVE

Ernest Temple Hargrove was born on December 17, 1870, at Laurel Lodge, Twickenham, in West London, to James Sydney Hargrove and Jessie (née Aird) Hargrove. He would have been the couple’s fifth child, however, two weeks before Hargrove was born, on December 3, 1870, his 18-month-old-sister, also named Jessie, died in the family home. Hargrove would be the fourth oldest of eight Hargrove children; ranking from oldest to youngest, they were: Constance, Norah, Sidney, Ernest, Percy, Herbert, Reginald, and Hilda. By all accounts, the family were close, and the home life was happy, with a “refined English atmosphere.”[24]

Hargrove’s paternal line included a great grandfather, Ely Hargrove, the writer of “Anecdotes Of Archery From The Earliest Ages To The Year 1791,” which provided a historical survey of Robin Hood, and grandfather, William Hargrove, who wrote “History And Description Of The Ancient City Of York.”[25] His father, J.S. Hargrove, was the family solicitor of John Horatio Lloyd, grandfather of Constance Lloyd, future-wife of Oscar Wilde. J.S. Hargrove “A gentleman in every sense of the word, clever with a cheery, amiable manner and whose friendship everyone appreciated,” and one of the directors of the Carl Rosa Opera Company.[26] Wilde himself would later write that it was for Lloyd that the Hargrove family owed much of their own “considerable wealth.”[27] Shortly before his marriage to Constance, J.S. Hargrove interviewed Wilde in his home, as Otho Lloyd, Constance’s nephew would later recall: “[Wilde] had an interview in chambers with Mr. Hargrove, the family lawyer, and, pressed as to his ability to pay, replied: ‘I could hold out no promise, but I could write you a sonnet if you think that that would be of any help.’”[28] In his later years, Hargrove would record his impressions of Wilde:

Many years ago I met him. I was very young, and what struck me about him chiefly was his bulk and his supercilious manner. Older men who had talked of him in my presence had admitted that he had genius, but they had ridiculed his eccentricity. I was confused but was too young in any case to judge for myself.[29]

Hargrove’s mother, Jessie Aird, was the daughter of John Aird—a distinguished engineer whose projects included the Crystal Palace, and the Royal Albert Hall.[30] John Aird, Jr., Jessie’s brother, and Hargrove’s uncle, was the M.P. of Paddington North. It was said that he “took his [political cues] from his friend and political godfather, Lord Randolph Churchill,” the M.P. of Paddington South; a family friend, neighbor, and father of Winston Churchill.[31] In addition to Aird’s feats of civil engineering, he was also a patron of the arts and Master Mason—being the first Master of London’s Evening Star Lodge.[32]

(Laurel Lodge c. 1875)[33]

Hargrove was baptized in the Church of England’s Holy Trinity Church, in Twickenham, on March 19, 1871, by the non-conformist vicar, Isaac Taylor.[34] The Hargrove’s would have certainly been aware of their Vicar’s unorthodox beliefs.[35] As Hargrove would later say, his family belonged to the Church of England, but he “couldn’t…believe in Hell and similar accepted theories of the creed.”[36] He received his education in various preparatory schools, including the prestigious Harrow School, where he admittedly “spent most of his time reading novels.” Upon leaving Harrow in 1886, Hargrove, who had studied for the Diplomatic Service, was then offered the opportunity to attend Cambridge University or travel abroad. Choosing the latter, the eighteen-year-old Hargrove toured Australasia, and Ceylon, before returning to London in the early 1890s.[37] It was in the summer of 1891, while on holiday in an English seaside resort, when Hargrove was first introduced to Theosophy, and subsequently had a powerful conversion experience.[38]

As for the Lord Harlech connection? On April 22, 1891, a week before the Annual Lodge of English Freemasons, the Prince of Wales presided over a charity dinner at the Savoy Hotel. Among the intimate selection of guests were John Aird and Lord Harlech. In his speech, the prince voiced his appreciation for the generous donation of J. P. Morgan to the charity event.[39] The connection goes deeper.

1895

By 1895 the home of Clem and Genevieve “became one of the most real and vital centers of the whole Theosophical movement.” It was W.Q. Judge’s habit to take Sunday dinner at the Griscom home, and to spend the evening there as their guest—“often he would stay for weeks at a time, going into the city with Mr. Griscom in the morning, but returning again in the afternoon.” At the time there was infighting among the leaders of the international representatives of the Theosophical Society. Over the winter of 1894-95 Clem was in communication with members of the Society sympathetic towards Judge, and it was at the Griscom house that the plans for succession and autonomy were drafted for the Convention of the American Section in the spring of 1895.[40] Shortly after the American Section split, Hargrove followed suit, and helped lead a group of English Theosophists who supported Judge. Later that summer Hargrove would make a second lecture tour of America.

S.S. St. Louis.

Hargrove purchased a ticket on the S.S. St. Louis, and would, along with C.A. Griscom Sr., depart from Southampton to New York on August 26.[41] The elder Griscom was in England for the debut launch of the St. Louis, his new ship. Present at the launch were Griscom’s friends, Prince Edward, and John Aird (Hargrove’s uncle,) the man who built the dock.[42] In 1895 the Red Star Line made significant changes in its European terminus when it moved from Liverpool to Southampton. This change of location (from Mersey to the English Channel,) placed the company in direct competition with the Hamburg-American and Norddeutscher Lloyd Lines, but diminished direct competition with larger comptetitors, the Cunard, and White Star Lines. This was a deliberate plan carried out by C.A. Griscom Sr., the owner of the Red Star Line, and the latter two rivals. In exchange for these yieldings, White Star and Cunard paid Griscom $30,000 a year, collectively, to cover the costs relocating to Southampton.[43] (In 1902 J.P. Morgan and Griscom would establish the International Mercantile Marine, and effectively create a shipping monopoly under which their former British competitors would be absorbed.)[44]

The Hargrove home (25 Lancaster Gate) was filled with the usual excitement that came with travel preparations. The steamer-chests were packed (and re-packed) with anxious expectations. Both Hargrove and his father, James Sydney, were about to embark on trips in the interest of the respective fields. For Hargrove it was Theosophy; for James Sydney it was in the interest of his clients, the Lloyd family, for, as the London papers reported, Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment had caused him bankruptcy.[45] Wilde’s fall from grace was almost total—almost. James Sydney received a prison-letter from Wilde around this time that was meant to be forwarded to the author’s wife, Constance Lloyd. James was pleasantly surprised when he discovered that Wilde’s letter was both sentimental and sincere. “One of the most touching […] letters that had ever come under my eye,” James Sydney said.[46]

Hargrove.

On the voyage over to America, Hargrove met Jane Potter Russell, the daughter of Henry Codman Potter—the 6th bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York (a person who was “more praised and appreciated, perhaps, than any public man in New York City’s long list of great citizens.”)[47] Jane was returning to New York with her husband, Charles Howland Russell, a man well acquainted with J.P. Morgan—Russell was partner in the prestigious law firm, Stetson, Jennings, Russell and Davis—also known as “J.P. Morgan’s Counsel.” [48] Upon arrival in New York, Hargrove stayed with the Griscoms. He would become more family than friend in the coming years. Young Acton Griscom would certainly have heard Hargrove’s views on Theosophy and King Arthur and Merlin as he grew up. Concerning the esoteric interpretation of the Arthurian romance, Hargrove writes:

Consider the story of King Arthur and his knights, and the Round Table. King Arthur existed. He may not have spelled his name just as we do, but he existed and so did his knights and the Round Table; and because, in their time Arthur and his knights represented the Theosophical Movement, they exemplified or symbolized universal truth, much as do the life and activities of the Avatar. The Grail reveals the very heart of Christianity—was and is that heart—as it was the heart of the Egyptian Lodge. The sword Excalibur, as was the sword of Joan of Arc, typified also by the law of correspondences, the sword of knowledge, the sword of spiritual understanding; so that when it was indrawn to the world of its origin (and you know what indrawal signifies) indrawn only through the persistence of the dying Arthur, by being thrown into the ‘mere’—there arose to meet it—“an arm, clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful.[49]

By 1896 William Quan Judge was dead. Hargrove became the President of the Theosophical Society, but by 1898 another schism occurred. A small faction, led by Hargrove and the Griscoms continued in New York. They, too, had their own Esoteric Section. After seven years of reclusive activity, the group remerged as a corporate body. One of their first such activities being Talks on Religion by Henry Bedinger Mitchell. The idea of the Theosophical Trinity (as espoused by the Griscom T.S.,) also appeared in the first book on meditation in the West (also written by Mitchell.)[50]

Russell Family.[51]

In 1908 the group made efforts to spread their teachings in the Chapel of the Comforter (10 Horatio Street,) the mission church of the Church of the Ascension. This would be the church where Acton would preach. Jane Potter Russell, who joined the Griscom T.S., would use her influence to help patron them administer the Chapel (Charles Howland Russell was also on the standing committee of the Church of the Ascension along with Clem.)[52] Other influential congregants who supported the Theosophists at the church included the writer and suffragist, Anne O’Hagan Shinn, the lawyer and defender of public parks, George Gordon Battle, and Theodore Roosevelt’s Presidential Secretary, William Loeb, Jr.[53]

Rev. C.C. Clark.[54]

Another member of the Griscom T.S., Clarence Carroll Clark, would also share in the pastoral work at the Chapel of the Comforter. An Associate Professor of English at Bryn Mawr College, Clark joined the Society after being inspired by the group’s Sunday School at the Chapel.[55]

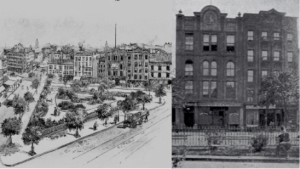

(Left) Jackson Square & (Right) 8-10 Horatio Street.[56]

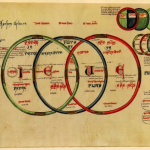

There was likely more to the story when Acton Griscom sent the letter to Lord Harlech in 1911. It was that year that Hargrove paid a visit to England to attend to matters connected with the death of his uncle, John Aird.[57] Perhaps he was reminded of the Lord Harlech’s manuscript at that time. It was that same summer that the Griscoms, Henry Bedinger Mitchell, and Hargrove spent some weeks living in the garden apartment of a hotel in Vevey. They associated with none of the other guests, as it was understood that they were “very busy studying occultism and must not be interrupted in their search for Truth!”[58] Whatever the case may be, many of the beliefs of the Esoteric Section of the Griscom T.S., now re-branded as The Order of the Living Christ, made their way into the Society’s literary journal, the Theosophical Quarterly. For the OLC, there were clear allusions in medieval works with their spiritual mission in modernity. With the understanding that human beings are septenary in composition—demarcated on a spectrum ranging from an animalistic nature of grossly material in the lower “quaternary” to the exalted ethereal trinitary (atma-buddhi-manas) the Christos—their hermeneutics expands the cross-cultural etiology of canonical religious works to re-contextualize European prehistory. C.C. Clark would write in 1912:

The Lady of the Lake, as Spiritual Essence, seems to be the emblem also of the Wisdom Religion. She dwells down in the deep that is calm whatsoever storms may shake the world, and when her lips move, the sound is as “the voice of many waters.” It is she who gives to Arthur his jeweled sword that bewilders heart and eye. …That is an eloquent illustration of the Theosophical attitude toward religion—ardor, tolerance, detachment. The religion into which we are born contains part of the [most ancient] wisdom known to men. It is the sword with which we are to fight. It is not to be surrendered until it has wrought its work; then, for all its jeweled hilt it must be returned to its source, in the deep. The three Queens who stand silent near the throne at Arthur’s coronation, and who conduct him to Devachan, may perhaps typify the higher spiritual and super-spiritual forces, the Triad, as distinguished from the lower Quaternary…Meditation…is to lead the soul consciously into communion with the Master. Tennyson symbolizes Meditation under the quest of the Grail.[59]

When compared with Acton’s own occult interpretations of romance, the harmony is obvious:

Romance appeals to the hero, and to the heroic; another clue as to its acting as a guide to the inner world; because, contained within the Greek traditions were echoes, and more than echoes, of the Third Race, when the Nirmanakayas reappeared “as Kings, Rishis and heroes,” as Madame Blavatsky tells us in The Secret Doctrine. The memory, and almost the deification, of heroes, from Greek and also Scandinavian sources, persisted into the period of the Middle Ages when Romance literature appeared. So, we find included the whole cycle of “quest” romances, depicting more or less ‘vaguely and generally the initiations of the knight or ‘hero.’” […] Must not the incarnation of every Avatar as set forth in theosophic teaching, bring with it a new, individual gift from the Lodge for the whole manifested universe? This new consciousness of the heart then, may be regarded as the distinguishing mark of the whole cycle of Christianity, which the classical age had never known. In its realization, the literature, the art, of our world, entered upon a new cycle, a new phase, the cycle of the heart, and of the self-consciousness, the maturity, which comes when we awake to the realization of love. Romance is, therefore, for us, an achievement of Christianity.[60]

Acton Griscom published his translation on Historia Regum Brittaniae in 1929. Charles Johnston, a journalist, and leading member of the Griscom T.S. would write note for the readers of the New York Times: “Those who go to Mr. Griscom’s book for information will be well repaid.”[61]

Interior of the Chapel of the Comforter c. 1925.[62]

[1] “Along Long Island’s Breeze-Swept Shore.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) July 9, 1911.

[2] United States, Selective Service System. World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. M1509, 4,582 rolls. Imaged from Family History Library microfilm.

[3] The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Oriental Hotel, Manhattan Beach, N.Y” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 14, 2023.

[5] Geoffrey of Monmouth; (trans.) Griscom, Acton; (ed.) Thorpe, Lewis. The History Regum Britanniae. Penguin. London, England. (2015): Introduction.

[6] Geoffrey of Monmouth; (trans.) Griscom, Acton. The History Regum Britanniae. Longmans, Green And Co. London, England. (1929): 31-37.

[7] Massock, Richard. “Seen And Heard In New York.” The Post-Crescent. (Appleton, Wisconsin) July 29, 1929.

[8] Griscom, Acton. “The Date of Composition of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia: New Manuscript Evidence.” Speculum. Vol. I, No. 2. (April 1926): 129-156.

[9] Frost, G. H. “Statement.” Engineering News. Vol. VIII (April 9, 1881): 147-149.

[10] Meade, Marion. Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York, New York. (1980): 132.

[11] Woodbridge, George. “‘Volunteer’ Or ‘Pressed’ Man.’” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. XXIII, No. 3. (January 1927): 248-253; “Obituary” The British Chess Magazine. Vol. X, No. 114. (June 1890): 229-230; Ancestry.com. Maine, U.S., Marriage Index, 1670-1921 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016; Woodbridge, George. “‘Volunteer’ Or ‘Pressed’ Man.’” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. XXIII, No. 3. (January 1927): 248-253.

[12] “An Epitome of Theosophy.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 3, 1892

[13] Marshall, Dexter. “Captains Of Industry: Clement Acton Griscom.” The Cosmopolitan. Vol. XXXV, No. 1 (May 1903): 57-59.

[14] Carosso, Vincent P. The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. (1987): 246-249; Burt, Nathaniel. The Perennial Philadelphians: The Anatomy of an American Aristocracy. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1999): 448.

[15] “Harbor Improvements.” The Times. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) September 1, 1881; “A Memorial.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) July 3, 1882; “Improving The Harbor.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) August 12, 1882; Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Seeman & Peters, Printers and Binders. Saginaw, Michigan. (1902); Flayhart, William H. The American Line: 1871-1902. Norton. New York, New York. (2000): 79-91.

[16] Morgan, Kenneth W. Memories. Unpublished. 257-277.

[17] “A Notable Reception.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) January 18, 1886.

[18] The Theosophical Movement 1875-1925. E.P. Dutton & Company. New York, New York. (1925): 171-172.

[19] Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. “A Stone of the Foundation.” The Theosophical Quarterly. XVII, No. 1 (July 1919): 9-21.

[20] “H.P.B. to C.A. Griscom Jr. on December 18, 1888.” Theosophical Society Archives, Adyar.

[21] “Hail! Wedded Love: A Long List of Marriages and Engagements in Philadelphia.” The New York Herald. (New York, New York) November 18, 1888; “Bride Is Niece Of Hancock.” The Boston Globe. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 19, 1889; “Wired From The City.” The Boston Herald. (Boston, Massachusetts) September 19, 1889.

[22] Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5447. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) Genevieve Ludlow Griscom; Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 5635. (website file: 1B:1885-1890) William Ludlow.

[23] Ludlow Griscom states it was an apartment on East 59th Street and 5th Avenue, most likely the Griscoms were living in the New Netherlands Hotel on 59th and Fifth Ave. The only residential building on that street until The Plaza Hotel opened until October 1890—four months after Ludlow was born. Davis, William E. Dean of the Birdwatchers: A Biography of Ludlow Griscom. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. (1994): 4-5.

[24] “Deaths.” The London Daily News (London, England) December 6, 1870. [“Births, Marriages, and Deaths.” London Observer, December 25, 1870. England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915. Registration Year: 1871. Registration Quarter: Jan-Feb-March. Registration District: Brentford. Volume 3A. Page: 63. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA.]

1881 England Census. Class: RG11; Piece: 656; Folio: 104; Page: 17; GSU roll: 1341152.

Kate Swan, “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists,” The New York World (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[25] Hargrove, Ely. Anecdotes Of Archery From The Earliest Ages To The Year 1791. E. Hargrove Knaresbro. York, England (1792); Hargrove, William. History And Description Of The Ancient City Of York. William Alexander. England (1818.)

[26] “Funeral Of Mr. Carl Rosa” The Morning Post (London, England) May 7, 1889; “The Funeral Of Mr. Carl Rosa” The Era (London, England) May 11, 1889; Aird, Charles. Depford, Toronto and Kingston: The Early Years of Charles Aird, Victorian Engineer. The Grimsay Press. Glasgow, Scotland. (2005): 332-333.

[27] Oscar Wilde to More Adey. April 7, 1897. In The Letters of Oscar Wilde. London, UK: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1962. 524-28.

[28] Otho Lloyd to Mr. Symonds. [MS. WILDE BX 32 FLD 20 Lloyd 1937 May 27]

[29] H. “Reviews: De Profundis, or the Breaking and Making of a Man.” Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. III, No. 2. (October 1905): 332-225.

[30] “Sir John Aird, Bart., M.P.” The Strand. Vol. XXX, No. 178 (November 1905): 453-455.

[31] “Great Engineer Was Sir J. Aird.” The Province. (Vancouver, British Columbia), February 11, 1911.

[32] Boyles, J.F. “The Private Art Collections of London.” The Art Journal Vol. 53 (1891):135-140.

“The Evening Star Lodge, No. 1719” The Freemason’s Chronicle. Vol. XIII, No. 327. (April 2, 1881): 229.

“Quarterly Communications Of The United Grand Lodge” The Freemason’s Chronicle. Vol. XXXIII, No. 843. (March 7, 1891): 152-155.

[33] “Houses Of Local Interest And Their Occupiers: Laurel Lodge.” The Twickenham Museum . Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/house-details.php?houseid=81&categoryid=1.

[34] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906/Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1906; Reference Number: dro/150/002.

[35] Isaac Taylor was Vicar of the Church of England’s Holy Trinity Church. While an incumbent in Holy Trinity in 1869, Taylor used his leisure time to write Etruscan Researches (1874) in which he contended the Ugrian origins of the Etruscan language. In 1875 Taylor began researching the origin of the alphabet. In Greeks and Goths: a Study on the Runes (1879,) Taylor argued that German runes were of Greek origin, which produced contention during his day. In 1883 he published The Alphabet, an Account of the Origin and Development of Letters in which he endeavored to prove that alphabetical changes were the product of evolution occurring in accordance with fixed laws, stating: “Epigraphy and paleography may claim, no less than philology or biology, to be ranked among the inductive sciences.” [The Encyclopedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 11th ed. Vol. XXVI. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, England. (1911): 469.] His paper on the Origin of the Aryans delivered at the British Association (1887,) and later developed into a book, notes that by the end of the 19th century, the racial characteristics of white skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes, were associated with the “Aryans.” Taylor writes: “The evidence of language shows that the primitive Aryans must have inhabited forest clad country in the neighborhood of the sea, covered during prolonged winter with snow. It has also been urged that the primitive Aryan type was that of the Scandinavian and North German peoples—dolichocephalic, tall, with white skin, fair hair, and blue eyes, and that those darker and shorter races of Eastern and Southern Europe who speak Aryan languages are mainly of Iberian or Turanian blood, having acquired their Aryan speech from Aryan conquerors.” [“The Aryans.” John Bull. (London, England) October 1, 1887.]

[36] Swan, Kate. “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists.” The New York World. (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[37] Welch, R. Courtenay. The Harrow School Register, 1801-1893. Longmans, Green, and Co. London, England. (1894): 567. (Hargrove studied under Assistant-Master, Charles Colbeck.)

[38] “Faces Of Friends: Ernest Temple Hargrove.“ The Path. Vol. IX, No. 6 (September 1894): 182-184; Kate Swan, “Preaching Theosophy to Socialists.” The New York World. (New York, New York) May 10, 1896.

[39] Anon. “United Grand Lodge of England.” The Freemason. Vol. XXVI., No. 1148. (March 7, 1891): 134-136; “Royal Albert Orphan Asylum.” The Times. (London, England) April 23, 1891; “The Prince of Wales and The Freemasons,” The Standard (London, England) April 30, 1891; “£1,000 In Twenty Minutes.” Charity. (London, England) June 15, 1891.

[40] “Prominent Long Islanders.” The Times-Union (Brooklyn, New York) July 2, 1897; Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. “A Stone of the Foundation.” The Theosophical Quarterly. XVII, No. 1 (July 1919): 9-21.

[41] “Proud Of Her Record.” New York Tribune. (New York, New York) September 1, 1895.

[42] “Death Claims C.A. Griscom; Noted Financier.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) November 12, 1912.

[43] “The New Graving Dock at Southampton.” Herapath’s Railway Journal. Vol. LVII, No. 2934 (August 9, 1895): 803-04; “Royal Visit To Southampton.” The Times. (London, England.) August 5, 1895; “Opening Of The New Graving Dock At Southampton.” The Hampshire Advertiser (Hampshire, England.) August 7, 1895; Middlemas, Robert Keith. The Master Builders. Hutchinson. London, England. (1963) 121-59; Flayhart, William H. The American Line: 1871-1902. Norton. New York, New York. (2000): 138-139.

[44] “The Ship Trust That Has Drawn Uncle Sam’s Fire.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) June 23, 1912.

[45] “Bankruptcy Of Oscar Wilde.” The Pall Mall Gazette. (London, England) August 22, 1895.

[46] Appendix C: A Visit from Mr. Hargrove. (1962). In Rupert Hart-Davis (Ed.), The Letters Of Oscar Wilde (pp. 871-872). New York, New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

[47] Sheerin, James. Henry Codman Potter, An American Metropolitan. Fleming H. Revell Company. New York, New York. (1933): 177.

[48] Howland Russell, Charles. Charles Howland Russell: 1851-1921. Self-Published. New York, New York. (1935): 58-59.

[49] “T.S Activities.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXXIII, No. 3. (July 1936): 201-254.

[50] “What is Theosophy?” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) December 20, 1891; “An Epitome of Theosophy.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 3, 1892; “Theosophy” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 17, 1892; “Theosophy.” The Detroit Free Press. (Detroit, Michigan) January 24, 1892; “Fifty Years” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XXIII. No. 3. (January 1926.) 209-211; Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. “Meditation.” The Theosophical Quarterly Vol. III, No. 4 (April 1906): 450-463; Mitchell, Henry Bedinger. Meditation. Quarterly Book Department, New York, New York 1906.

[51] Howland Russell, Charles. Charles Howland Russell: 1851-1921. Self-Published. New York, New York. (1935): 60,68.

[52] Howland Russell, Charles. Charles Howland Russell: 1851-1921. Self-Published. New York, New York. (1935): 32.

[53] “Society Home and Abroad.” The New York Times. (New York, New York) December 3, 1911.

[54] Charles Carroll Clark, Episcopal Priest of the Chapel of the Comforter, Greenwich Village, ca. 1920. Clarence Carroll Clark Papers (MS 393). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

[55] “Bryn Mawr College.” The Boston Evening Transcript. (Boston, Massachusetts) October 3, 1907; Clark, C.C. “The Chapel of the Comforter, Greenwich Village, New York.” Clarence Carroll Clark Papers (MS 393). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

[56] Parsons Jr., Samuel. “The Evolution Of A City Square.” Scribners. Vol. XII. (July-December-1892): 107-115; King, Moses. King’s Handbook of New York City: An Outline History and Description of the American Metropolis. Moses King. Boston, Massachusetts. (1892): 519.

[57] Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, 8892 rolls. NAI: 300346. Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service; National Archives at Washington, D.C.

[58] Thompson, Juliet. The Diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimát Press. Los Angeles, California. (1983): 192-194.

[59] C.C. Clark. “Theosophy and Secular Literature.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. X No.1. (October 1912): 129–135.

[60] Griscom, Acton. “Romance.” The Theosophical Quarterly. Vol. XVIII, No. 2. (October 1920): 117-125.

[61] Johnston, Charles. “Exploring the Sources of The Arthurian Romances: Acton Griscom Seeks to Determine the Truth About the Famous “History” of Geoffrey of Monmouth Geoffrey of Monmouth” The New York Times. (New York, New York) July 21, 1929.

[62] Chapel of the Comforter, Greenwich Village: Interior view of alter and statues of angels, ca. 1925. Clarence Carroll Clark Papers (MS 393). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.