From its conquest by the Ottomans in 1453 until the official end of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, Constantinople, renamed Istanbul, was their capital.

The Ottoman Empire reach its zenith under Süleyman (or Suleiman) the Magnificent, who reigned from 1520 to 1566 (roughly overlapping with King Henry VIII of England, “Bloody Mary,” and Queen Elizabeth I, who, compared with his vast domain, were mere petty chieftains). The name Süleyman is the Turkish (and more or less the Arabic) equivalent of the English Solomon. I personally prefer Süleyman to Solomon by a little bit. Both, though, are far preferable to the Hebrew original, Schlomo. (I can’t help but think of Schlomo the Schmuck. Not a very dignified name for an Israelite king or, for that matter, for an Ottoman sultan.)

Shortly after the reign of Süleyman, though, the Empire began to decline. Very, very slowly. For the last century of its existence, it was commonly known among Western diplomats, politicians, and writers as “the sick man of Europe.” Why? Because it lingered—ill and dysfunctional, but not dead. It can be said, that, from the founding of the Ottoman state through Süleyman, the Turks were ruled by roughly ten extremely effective (though not necessarily saintly) sultans. With his departure, though, they entered into a period where they were ruled by roughly an equal number of ineffective sultans.

By the way: What does the word sultan mean? It comes from the Arabic word سلطة sulṭah or sulṭa (“power,” “authority”), and suggests that the Ottoman rulers originally made no attempt to hide the fact that their political power did not derive from any religious mandate. (One thinks of Mao’s famous dictum, that “Political power flows from the barrel of a gun.”) Later, though, during the period of Ottoman expansion, they began to desire religious legitimacy. Thus, after Sultan Selim I conquered Mamluk Egypt in 1517, Ottoman rulers claimed the authority of the “caliph,” the vicarious stand-in for the prophet, that had begun with Abu Bakr shortly after the death of Muhammad and that had eventually found its way (if you’re inclined to believe the medieval propaganda) to Egypt. Seeming to support the Ottoman sultans’ claim to caliphal authority was the fact that, with the conquest of Mamluk Egypt, they inherited the Mamluk sultans’ title of “Defender of the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina.”

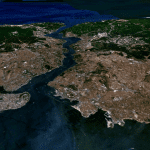

Back, though, to Istanbul: Today, although it remains Turkey’s largest city, Istanbul is no longer the nation’s capital. On 23 April 1920, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey was established in Ankara, which became the headquarters of the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence. Upon the establishment of the new Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1929, Ankara became the new Turkish capital, replacing Istanbul. Although it is a relatively new national capital, though, Ankara is actually quite ancient, going back to the Hattic civilization which was then absorbed by the Hittites around 2000 BC. For centuries, it was the principal city and capital of Galatia (home of the biblical Galatians). In one of the many forms of its name, Ankara has given us the Angora wool that is shorn from Angora rabbits, the long-haired Angora goat from which we obtain mohair, and the Angora cat.

Moving the seat of government inland to Ankara from the ancient imperial capital of Constantinople/Istanbul, where it had resided for very nearly sixteen centuries, was entirely congenial to the program of modernizing reforms laid out by Mustafa Kemal (ca. 1881 – 10 November 1938), who is generally acknowledged as the father of modern Turkey or Türkiye. He was a secularizer and a Turkish nationalist who wanted to separate Turkey from its imperial—multinational, multiconfessional, multiethnic, multilingual—past and concentrate on its Turkishness. To do so, among many other things, he completely abolished the caliphate in 1924, freeing the ruler of the new Turkey from an entanglement or responsibility beyond its borders.

Since then, many Islamic fundamentalist groups, not least among them al-Qa‘ida and ISIS, have sought to reestablish the caliphate. Most of the Islamic world, however, although shocked and dismayed by Mustafa Kemal’s abolition of the caliphate, realized fairly soon that the title’s disappearance made little practical difference. The office of caliph hadn’t possessed real, independent power in the Islamic world as a whole for many centuries. It had been a symbol, merely.

Mustafa Kemal also changed the alphabet in which Turkish was written from a modified Arabic script (which, truth be told, was not well suited to representing Turkish, a language featuring a complex system of vowels and vowel harmonies) to a modified Roman one. This had the (likely deliberate) effect of relatively quickly creating a new generation that, without special training, was flatly unable to read, understand, or even to sound out old documents, including the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad.

Furthermore, Mustafa Kemal required Turkish citizens to adopt surnames, which they had seldom used before. Instead, they had tended to follow the Arabic naming system, with its patronymics and its descriptive titles (e.g., Abu Farid Mustafa ibn Salim al-Halabi, “Father of Farid, Mustafa, son of Salim, the one from Aleppo”), or even just to use a single name. Mustafa Kemal had originally just been Mustafa, until, it is said, a teacher gave him the name Kemal (“complete,” “perfect”) in order both to distinguish him from a classmate who was also named Mustafa and to signal his excellence in mathematics and in his other studies. When the time came to adopt a surname, he led the way by adopting the name Atatürk. “Father of the Turks.” It was officially bestowed upon him by the Turkish parliament in 1934, and it is the name by which he is most commonly known to this day, in the Middle East and outside of it.

We shouldn’t be surprised, by the way, that the Turks hadn’t yet adopted surnames in the Western sense. After all, large parts of the West itself were slow to adopt them. It wasn’t all that long ago in Scandinavia, for instance, that my own surname, Peterson, would have indicated that my father was named Peter. And, before they became surnames, words like Cooper, Porter, Carter, Taylor, Sawyer, Collier, Wagner, Miner, Knight, Farmer (German Bauer), Smith (German Schmidt), Carpenter (Zimmermann), and Miller (Müller) indicated the ways in which we made our livings. And names like York and Forrest and Ford and Woodsand Fields and Rivers and Banks suggested something of where we were from.

Our tour group is almost entirely arrived by now, with most coming in this evening. Those of us who arrived yesterday, though, spent the day in and around the late-Ottoman Dolmabahçe Sarayı, followed by a visit to the Edirnekapı quarter of Istanbul’s Fatih district, which is the very section of the famous Theodosian walls of ancient Constantinople where Sultan Mehmet’s Ottoman troops breached Byzantine defenses on 29 May 1453, thereby conquering the city. Afterwards, we went to the Galata Tower. Then, following dinner back at our hotel, some of us went to the three-hundred-year-old Cağaloğlu Hammamı. I just did the foot massage.

Posted from Istanbul, Türkiye