“Enthroning the Daughter of Zion: The Coronation Motif of Isaiah 60-62,” in The Temple: Ancient and Restored, written by Carli J. Anderson

Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article originally appeared in The Temple: Ancient and Restored, Proceedings of the Second Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 25 October 2014 (2016) edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. For more information, go to https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/the-temple-ancient-and-restored/.

For the time that I expected to spend in the waiting room of a medical appointment today, I picked up a copy of Eric H. Cline, Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), that has been on my shelf for quite a while, just begging to be read.

First of all, I want to say that I really like it. It’s quite lucid, and it’s appropriately concise. One might almost call it “brief.” Its explanations are very clear. Another aspect of the book that, so far, I think some of you might enjoy is its brief history of the discipline of biblical archaeology, of its origins and development.

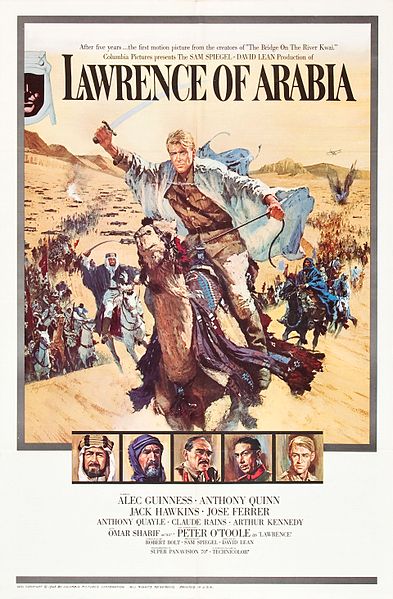

Did you know, for instance, that T. E. Lawrence (most famous, of course, from his World War One exploits as “Lawrence of Arabia”) was an Oxford-trained archaeologist? (I did, but I’m a bit weird that way.) Did you know that he was hired in 1914 by the Palestine Exploration Fund to survey sites of archaeological interest in southern Palestine? He had already, by that time, been involved in excavations at Byblos, in what is today Lebanon, at Carchemish in which is now northern Syria, and with the great Sir William Flinders Petrie in Egypt.

In a period of less than two months, Lawrence and his companion Leonard Woolley (who would later be knighted and become very famous for his dig at Ur, in northern Iraq) had surveyed and recorded a large number of the archaeological sites and identified many of the caravan routes — both ancient and medieval — in the Negev Desert and in the Wadi Arabah. They published the results of their work as The Wilderness of Zin, which is still useful and available in print. And, meanwhile, they had mapped the possible routes that an invading Ottoman army might take to reach the British stronghold of Egypt in the event that war broke out. Which, of course, it did. (See the film Lawrence of Arabia. Preferably on a big screen.)

Later, the enormously influential rabbi and archaeologist Nelson Glueck conducted an important archaeological survey of the Sinai, the Negev, and the Jordan Valley that was not only very helpful to scholarship but of great value to the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of today’s Central Intelligence Agency. For he was not only president of Hebrew Union College, but a spy. He was looking for sources of potable water and for escape routes that Allied forces might require if the Germans were successful in seizing control of North Africa and then decided to invade Palestine.

There has long been a political dimension to archaeology in the Holy Land. For generations, Israeli archaeology has sought to chronicle and substantiate the Jewish claim to Palestine. I don’t think it coincidental that the legendary late Israeli military hero and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was a passionate amateur archaeologist.

Moreover, and although I don’t think that there’s anything sinister about the fact, I doubt that it’s entirely coincidental that Yigael Yadin, son of the important archaeologist Eleazar Sukenik and himself one of the greatest Israeli archaeologists of the twentieth century, served as Israel’s “Head of Operations” during the 1948 War of Independence, in which role he was centrally involved in the military decisions and strategy of that war, nor that, from 1949 to 1952, as he served as Chief of the General Staff of the Israeli Defense Forces. Later, during my time as a student in Jerusalem in 1978, I went with my then teacher and now long-time friend S. Kent Brown, who had been Yadin’s graduate assistant when Yadin was a visiting professor at Brown University in Rhode Island, to visit Yadin in his office at the Israeli Knesset. At the time, he was serving as Israel’s Deputy Prime Minister.

Professor Cline does a good although very concise job of illustrating how international political ambitions and rivalries played a role more generally in the archaeology of the Holy Land from the very beginning. In that regard, if in no other, the adventures of Indiana Jones aren’t quite as far from the truth as one might initially imagine them to be.

Such issues arise elsewhere, too. In the days of Gamal Abdel Nasser, for example, who was an advocate of pan-Arab nationalism, the emphasis was on Arab unity, and Egypt was the “United Arab Republic.” For a brief period of roughly three years, from 1958 to 1961, Syria was in a union with Egypt, so the name made sense. It persisted, however, until 1971, a year after Nasser’s sudden and unexpected death from a heart attack in 1970. (Briefly, too, something called the “United Arab States” included not only Egypt and Syria but the Kingdom of Yemen. That, though, was dissolved already in 1961.) After the end the United Arab Republic, the new Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, determined that he would concentrate on Egypt itself. So the country became known as the “Arab Republic of Egypt.” And I’ve noticed, over the years, that the rhetoric surrounding Egyptian identity has changed with the varying international political climate. After Sadat’s dramatic peace overture to Israel and the virulent rejection of it that came from other Arab states, he tended to downplay Egypt’s “Arabness” and to play up the glories of its millennia-old history and civilization. While the “Arabs” were wandering about the desert in tents, he would sometimes muse, the Egyptians were building the pyramids. Nowadays, of course, many Islamic fundamentalists in Egypt not only want to downplay that pagan pharaonic past, but also to deemphasize “Arabness” in favor of a common Islamic identity.

And so it goes.